The Outer Worlds, a science fiction action adventure role playing game, is a spiritual successor to Fallout: New Vegas. While Bethesda developed most of the revamped Fallout series, Obsidian Entertainment developed Fallout: New Vegas, widely considered to be amongst the best of them. Obsidian has done it again.

The Outer Worlds, a science fiction action adventure role playing game, is a spiritual successor to Fallout: New Vegas. While Bethesda developed most of the revamped Fallout series, Obsidian Entertainment developed Fallout: New Vegas, widely considered to be amongst the best of them. Obsidian has done it again.

The “Fallout” series contrasted blithe advertising against bleak nuclear devastation to show how consumerism had detached us from reality, like a subtler Rad Bradbury’s There Will Come Soft Rains. This contrast was particularly evident of the pro-industry, pro-American optimism and nationalism of the 1950’s, whose aesthetic the “Fallout” series borrowed for its retro-futuristic style.

However, The Outer Worlds takes this in a different direction. It retains the futurist 1950’s aesthetic but immediately confronts the player with capitalist authoritarianism. What starts as kitsch descends into absurdity then horror as the bureaucratic oppressiveness and repetitive, vapid advertising jingles grate.

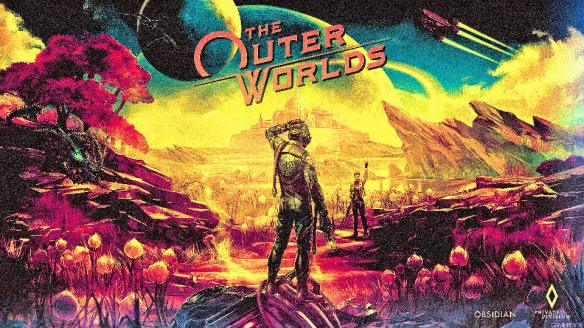

Meanwhile, the almost surreally vibrant alien landscapes replace the bleak, practically monochromatic art style of the “Fallout” series’s post-nuclear war America. The scene is relatable enough with plants and water and clouds. However, the plants are strange puffballs and oversized mushroom trees. While the pinks and oranges of clouds in a sunset are beautiful, they are set beneath the red rings of an alien gas giant.

This alienness extends to its soundtrack. As the character first steps onto a planet, the music has sequences of solos followed by answers from the broader orchestra after unsettling, awkward pauses. Even the title theme played over the main menu starts with two flutes playing at their lowest register, giving an ethereal feel, followed by a subdued, almost mournful but resolute motif.

Both the music and art differentiate scenes and anchor the player in a location. For example, a visual overload of neon assaults the senses as the door to the promenade on the Groundbreaker recedes. The bass riffs with subtle harmonica overtones played when entering the Edgewater are reminiscent of the wild west. The intense primary colours of Terra 2 (green grass, blue water or red lava and rings) contrast against the yellow, sulphurous tones of Monarch and the dull, monotonous grey of Byzantium.

Like the “Fallout” series, The Outer Worlds thrusts the player as an outsider into a plot that subverts the status quo. Whether this subversion is for the better or worse is determined by the player’s choices. The ultimate enjoyment of the game is exploring choice and effect. A cathartic, offensive approach is an option but finding the best outcome, typically a non-violent compromise, is often harder, requiring exploration and lateral thinking.

Mechanically, The Outer Worlds is generally an evolution from standard science fiction RPG fare. As the character advances through levels, they increase skills and choose special abilities, called perks, that give bonuses. A time dilation mechanic replaces “Fallout”’s VATS, allowing the player to aim at discrete body parts to inflict penalties like blindness for a headshot. There are crafting mechanics for those so inclined.

However, the “flaw” system is noteworthy. They allow taking penalties for a bonus perk. As tabletop RPG game designers have known for some time, imperfect characters are often more fun to play than perfect ones. Flaws enshrine role playing decisions into mechanics and give a greater challenge. They are optional but must be earned. For example, you can gain phobia of a particular species, represented by temporary penalties, by fighting them too often.

The Outer Worlds also adds a new stealth mechanic by adding a personal holographic projector. Instead of save scumming your way around guards, after finding the appropriate MacGuffin, you disguise yourself as one of them but with a strict time limit. When it expires, you can renew the time limit by convincing a guard to let you pass, a task that becomes more difficult each time you try. It makes a welcome change of pace.

As for side quests, the inclusion of Pavarti’s love affair with Junlei as most fleshed-out companion quest will wrinkle the nose of some as political correctness. However, her endearing awkwardness, the relationship’s slow build and the absence of physical love scenes create a restrained and mature approach often lacking in earlier RPGs like Mass Effect.

Including Scientism, a religion to underpin the authoritarianism is a brilliant piece of world-building. Why justify people’s caste-like working conditions when you make it religious duty? Why circumvent science like other religions when you can justify fate with mathematical determinism? More exploration of these through the eyes of your companion Vicar Max or the NPC Graham would have been fascinating.

However, the purpose of religions like Scientism and its polar opposite, Philosophism, is not existential introspection like in Nier: Automata. Instead, they are contrasting strawmen, both with good and bad points. They allow the player to plot themselves on a spectrum and appreciate significant decisions are often between imperfect options.

The Outer Worlds is also not without humour. While it eschews overt pop culture references to emphasise the setting’s remoteness, it does not take itself too seriously. The deadpan sarcasm of ADA, your ship’s onboard computer, sometimes takes a moment to process but leaves a wry smile. The conversation options to persuade guards to let you pass alludes to Obi-Wan Kenobi’s “these are not the Droids you are looking for” from Star Wars. The name of your ship, the “Unreliable”, is self derogatory. There is even an achievement for shooting at opponent’s crotches during time dilation.

The Outer World’s single-player campaign as twenty to thirty hours of gameplay, depending on how much you explore or indulge the side quests. This game, a homage and evolution of the “Fallout” series, is lovingly crafted and I look forward to the inevitable sequel.