Star Wars Jedi: Survivor (or Jedi: Survivor) is a science-fiction adventure RPG developed by Respawn Entertainment, the same company that created the prequel, Jedi: Fallen Order. Thankfully, Jedi: Survivor is a worthy sequel, improving on the prequel in every way.

You play Cal Kestis, a Jedi Knight, continuing his fight against the Empire. Retreating to the backwater planet Koboh after a mission on Coruscant goes horribly wrong, Cal stumbles upon a forgotten planet that could be a hidden refuge for those he holds dear.

At first glance, Jedi: Survivor appears mechanically similar to Journey to the Savage Planet, the previous game I played. Both are exploration traversal games set on alien planets, where you wander, discover new areas, fight foes and collect resources. You have the traversal mainstays like the double jump and a grappling hook. You gain upgrades as you progress, allowing you to access more areas, defeat stronger enemies and complete challenging timed events.

However, the similarity ends there. Journey to the Savage Planet is about fun with cartoonish violence, densely packed levels and self-aware humour. Jedi: Survivor is about mastery, both in combat and traversal.

Jedi: Survivor‘s combat is “Souls-like”. Enemies hit hard and often outnumber you. Success requires learning enemy abilities and correctly timing parries and dodges. Combat is challenging, meaning you will die frequently as you learn and experiment, but not punishing, assuming you unlock shortcuts to shorten the journey back from the respawn point.

Jedi: Survivor adds two new lightsaber stances to the versatile single-blade, fast dual-blade and defensive double-blade stances from Jedi: Fallen Order. The crossguard stance, inspired by Kylo Ren’s lightsaber, adds a slow but damaging greatsword. The blaster stance, as its name suggests, has Cal Kestis wielding a blaster and lightsaber, fulfilling Han Solo or Wild West gunslinger-style fantasies.

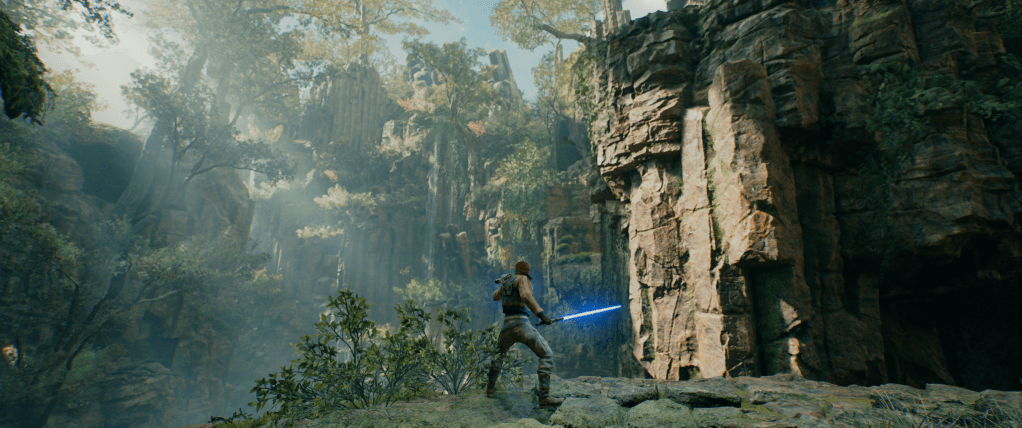

Jedi: Survivor is also about exploration, with big, broad maps filled with traversal puzzles, riding mounts and even a speeder bike sequence.

Jedi lend themselves well to this style of play. Ever since Luke’s first training scene on Dagobah in The Empire Strikes Back, Jedi have demonstrated themselves to be acrobatic and athletic. They often befriend local wildlife.

Structurally, Jedi: Survivor has peaks of action during intense, story-relevant scenes and boss fights, followed by more leisurely downtime. Players can spend these breaks exploring, collecting or bounty hunting. You can expand their very own cantina via recruiting NPCs, fishing (by interacting with an NPC that appears at water), finding music tracks for the DJ, collecting plant seeds to fill a garden or scanning defeated opponents to use in holotactics games. Companions sometimes join Cal for story-specific sequences, often opening new areas or teaching Cal new abilities.

Jedi: Survivor‘s storyline explores purpose, sacrifice, friendship and acceptance. The story is told mainly through cutscenes, conversations with the many supporting characters and force echoes, which reveal past events or conversations. While it deals with galactic-relevant events and drops a few familiar names, the story focuses mainly on its characters, creating a personal story that tugs at heartstrings.

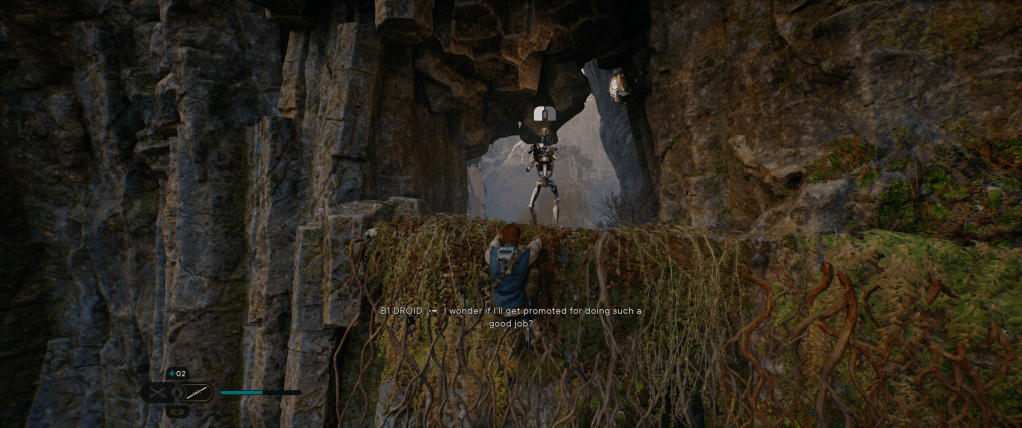

Just like in the movies, Jedi: Survivor has occasional bursts of humour, like the overheard banter between enemies, particularly the B1 droids introduced in the prequel movies. Struggling through tough fights to face Rick, the door technician, will bring a smirk to your face.

A now stubbled Cal even has a brush with romance, a taboo subject for Jedi, but handled tastefully and respectfully. It adds a little sexual tension, like in The Empire Strikes Back.

However, Jedi: Survivor‘s themes are only deep enough to motivate you, and not a genuine examination like in Cyberpunk 2077 or The Witcher series. While minor characters can sometimes point you to interesting parts of the map, there are no true side missions or plot choices to add depth or consequence.

Jedi: Survivor is unmistakably a Star Wars game, and not just because it involves lightsaber-wielding Jedi using the force against the Empire and other instantly recognisable tropes. Jedi: Survivor continues the themes of droids as people and good fighting an asymmetric battle against a seemingly overwhelming evil. Cal’s ship, the Mantis, is a Millennium Falcon equivalent, a similarly delapidated but faithful steed carrying Cal and his pseudo-family from stage to stage.

The game is faithful to Star Wars in its environment design. Most worlds you visit are technological backwaters, where primitive ochre and stone buildings are juxtaposed with automatic doors, artificial lighting and droids. Like the movies, Jedi: Fallen Order mixes the familiar with the alien or technologically different.

The colour palettes are muted pastels. Gone are the brilliant greens of Kashyyk and the purples of Dathomir in the first game. Instead, there are the reds of Dune-like Jedha, the greys of Coruscant and Californian scrub-like Koboh. These palettes give the game a realistic feel and make each location clearly unique.

Jedi: Survivor has Star Wars‘ audio pedigree. Stephen Barton and Gordy Haab return from Jedi: Fallen Order to deliver an emotional, epic, orchestral soundtrack that evokes the best of John Williams. The distinctive lightsaber whoosh, blaster ping and AT-ST foot clang abound.

Like Jedi: Fallen Order, Jedi: Survivor respects Star Wars as an intellectual property and a genre. It is neither derivative nor uninteresting and avoids redefining elements for its own ends. NPCs, like Darth Vader, are used faithfully. Jedi are noble, humble and capable, not the flawed, inflexible strawmen presented in later works.

Cal is a young male Jedi with a droid sidekick like Luke Skywalker. However, Cal is motivated by survival and the desire to protect, rather than seeking adventure or saving his father. Cal’s later dabbles with the force’s dark side present it as seductively and terrifyingly powerful while implying Cal’s greatest challenges lie ahead.

This series has cemented itself as a worthy addition to Star Wars lore and canon. At about thirty hours to finish for a storyline-only playthrough, Jedi: Fallen Order is about double the length of Jedi: Survivor. Those looking for a challenging and faithful Star Wars RPG will relish it. I look forward to the inevitable sequel.