An Elite Dangerous ship build.

Goals

Create a ship to:

- Support other ships by healing shields and hulls. Elite is a game with few niches, but engineering opens a few more.

- Heal teammates in Thargoid interceptor fights.

- Be a viable PvE combat ship when not healing.

- Require no unlockable modules, reputation or rank.

Build

Links: Coriolis or EDSY (have your preferred one open as you read the guide for easy reference)

While it sits beneath the firepower and shields of the Fer-de-Lance or Mamba, the Krait Mk II’s huge class 7 Power Distributor and copious optional internal module space make it ideal for less combat-specific roles like healing. It is faster and more manoeuvrable than the Python, and the Python’s extra class six slot matters little for this use.

To heal:

- Power Distributor: The Power Distributor is probably the most critical module for healing ships. It is essentially three large capacitors, one for systems (including shields), engines and weapons. The larger the weapon capacitor, the longer weapons can fire. Hence this build uses Weapon Focused (blueprint) with Super Capacitors (an experimental effect that increases the recharge rate).

- Regenerative Sequence on Large Lasers: This build has beam lasers, all with Regenerative Sequence. Instead of damaging teammates’ shields, this experimental effect heals them by the weapon’s damage output. It damages hulls and other targets’ shields.

- Efficient Large Lasers: This build uses the Efficient blueprint. This blueprint significantly reduces their power requirements and heat production while giving a slight damage increase.

- Healing: The power distributor and beam weapon engineering create a ship that can fire all five lasers at a target for 24 seconds, assuming four pips to weapons and a full capacitor. At 800 m or less range, this heals or does almost 100 damage per second.

- Repair limpet controller: Limpets launched by a Repair Limpet Controller heal hull damage. The limpets are slow, flying around 250 m/s, so the teammate may have to slow or stop for the limpet to catch up. Between fights is the best time to use them. Unfortunately, they cannot repair module damage or canopies. Teammates will have to use AMFUs for that. Do not forget your limpets!

Defensively, this build is pretty standard:

- Lo-Draw Shield: The shield has Lo-Draw rather than Fast Charge. Fast Charge draws too much power, resulting in a slower shield recharge than Lo-Draw.

Variants

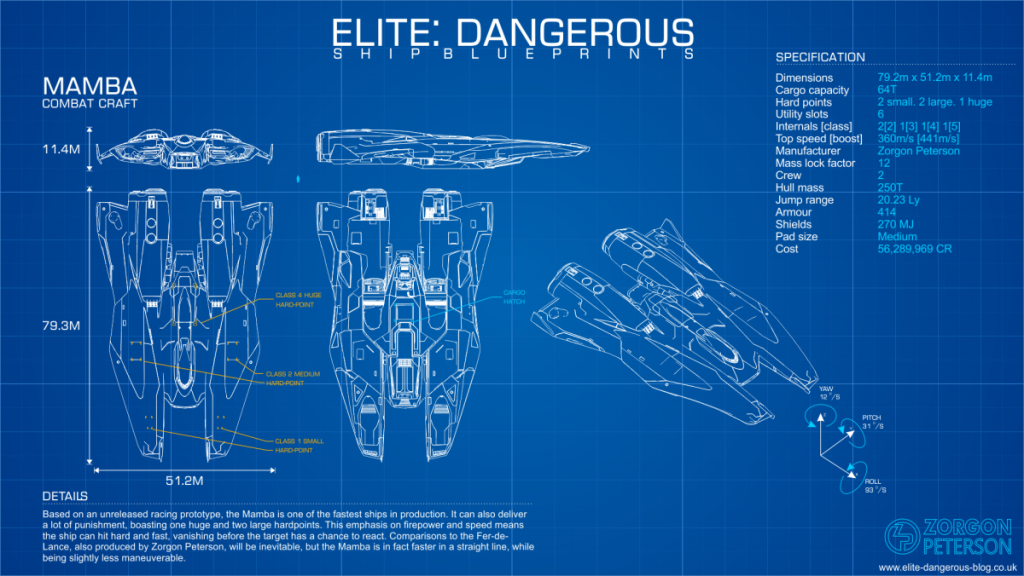

The same variations with the Mamba apply here, such as replacing Module Reinforcement Packages with the guardian versions, Prismatic Shields and cost reduction.

- Alternative laser experimental effect: Another option is Concordant Sequence, which increases shield regeneration to ten times its usual value for ten seconds. However, this is less effective on ships with Prismatic Shields due to Prismatic Shields’ low regeneration rate. If you regularly wing with ships that do not use Prismatic Shields, replace the experimental effect on one of the Medium Lasers with Concordant Sequence. The Concordant Sequence buff is unrelated to the weapon’s damage and does not stack, so use the smallest weapon possible.

- Alternative laser blueprint: Long Range instead of Efficient will allow healing over long distances. It can help a spread-out team. However, the increased distributor draw and heat generation mean you cannot fire for nearly as long.

- Anti-xeno healing: Replace the Repair Limpet Controller or 5D Hull Reinforcement with a Decontamination Controller. Replace the 4E Cargo Rack with a 4E Corrosion Resistant Cargo Rack if you want to pick up Thargoid hearts. If healing larger ships like Federal Corvettes and Imperial Cutters, swap the gimballed lasers for fixed for higher heal or damage rates.

- Fighter: Equip a fighter hanger for more firepower, particularly one with plasma weapons for better hull damage. A fighter also provides an alternate target when engaging wings of smaller ships. It may cause lag or “rubber-banding” when in a team but is useful when soloing.

Solo Tactics

- Close combat: As the damage fall-off of a large laser is only 800m, you need to get close to get the full damage. Throttle up if the target is over 1.5 km away to get close, then throttle back into the blue when they do so you can turn faster to maximise time on target. Use pre-turning or “landing gear turns” if needed.

- Favour smaller ships: Your beam lasers, being purely thermal damage and having moderate Armour Piercing values, will be most effective against medium and smaller ships. Vaporing small ships and fighters with this build is fun. If you must fight larger ships, target sensitive modules like Power Plants to avoid drawn-out fights.

- Longevity: Without ammunition, the limiting factor to combat with this build is hull damage. Engaging medium or light targets means you can fight indefinitely.

- Power (Pip) management: Put two pips in systems and four pips on weapons to maximise the laser firing duration. You will need three or four pips in shields to avoid draining the system capacitor after they drop.

Team or Wing Tactics

- Healing: Keep an eye on your teammates’ shields and top them up when needed. Unengineered or lighter ships will require more attention. Use a hotkey to select the teammate, get their location from your radar, put pips to engines, turn toward them and throttle up. Do not fly directly at them because you may run into them. Put pips into weapons to heal for longer.

- Anti-Thargoid interceptor healing: Ensure you are in a team with the tanks or those you want to heal. Keep the weapon distributor topped up and ready to heal a teammate through a lightning attack. Four pips are required when healing against a thargoid interceptor’s lightning attack. Outrun caustic missiles or use a decontamination limpet on yourself when needed. If you get attacked by a thargoid interceptor, fly to the nearest tank and hide behind them while the tank regains the interceptor’s attention.

- Anti-shield: As mentioned above, five beam lasers are an unbalanced weapon loadout. Having to get close to targets also risks drawing attention. Therefore, focus on shielded targets, particularly those using Shield Cell Banks, then fire sparingly on hulls. Focusing keeps your weapon capacitor charged for healing or the next shielded target.