Have you ever watched a movie or TV show and wanted to pause and marvel at a scene? It may be beautiful, showing off an artful mix of colour and design. It may be complex, requiring time to appreciate the detail. It may capture a moment that creates strong feelings or thoughts.

I love taking screenshots in video games. Not all video game graphics are lifelike or realistic, but even retro or pixel graphics have their beauty, such as the screenshot from Cloudpunk below. The definition of “realistic” also decays as each new generation of hardware increases fidelity.

Why take screenshots? I enjoy it. Arranging a good scene and admiring it as a screenshot is fun. This admiration is called “sense-pleasure”, a term coined in the original Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics game design framework. Some game developers have screenshot competitions and communities. Winning is fun, as is sharing a common interest. Trying to take good screenshots also allows me to appreciate the effort developers put into games, looking at games and visual media through different eyes.

Taking good screenshots is simple: play games, take lots of screenshots, review them, decide which ones are the best, try to get more of those, and repeat.

That leaves two questions. The first is “Which games should I take screenshots from?” The second is “What makes a screenshot good?”

The answer to the first question is also simple: play whatever games you enjoy. That said, some platforms, such as PCs, and game types, like 3D open-world games, are more conducive to taking beautiful screenshots. High-end PCs have higher resolutions and are capable of better graphics. The developers of 3D open-world or similarly expansive games often create visually appealing worlds.

Some graphics capabilities require special attention. Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are more of an experience, something a static screenshot cannot capture. Screenshots from High Dynamic Range (HDR) displays are often too bright, at least in non-HDR file formats.

Screenshots of glitches, memes or schadenfreude are often spontaneous. These can be fun. They have their place. However, these tend to be unpredictable and their popularity fleeting.

Answering the second question, “What makes a screenshot good,” is more difficult. Someone with art training could write volumes on what makes a good painting or scene. However, some general advice I found helpful follows.

The human eye is usually drawn to specific places when playing a game. Players have fractions of a second to decode a busy scene and determine what to do next. The game designer wants to emphasize where to go next or the boss’s weak points.

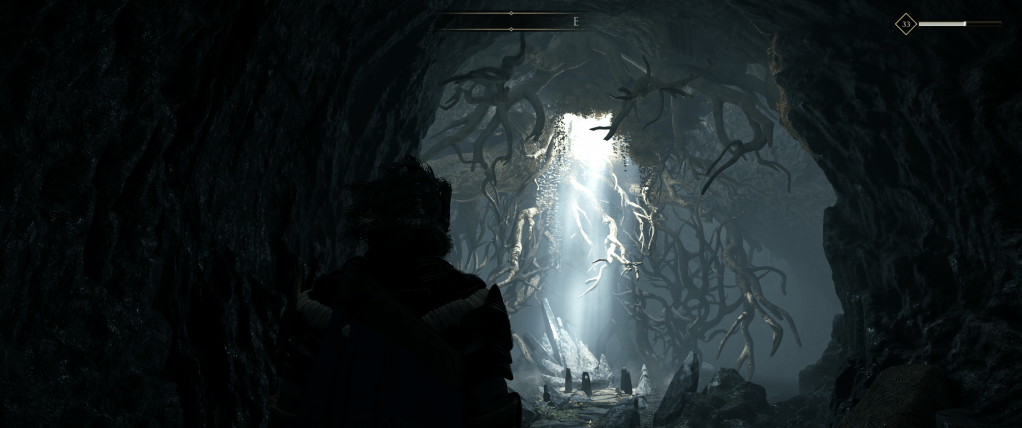

The above screenshot from Greedfall shows how the developer can unsubtly force the eye to focus somewhere. The light filtering from above among the dangling roots directs the player while hinting at this place’s history and significance.

However, the human eye can take its time to appreciate a screenshot. Treat each screenshot as a diorama. People view a screenshot holistically, like a painting. Arrange interesting things around the image or, if there is a single focus, ensure it is unique or intriguing enough to hold attention.

This screenshot shows a beautiful fusion of elements. The blue exhaust from the Asp Explorer (spaceship) heading towards the ringed planet matches the light of the eclipsed blue-white star. The edge of the Milky Way galaxy shows behind. This fills the image, meaning there is something interesting to look at everywhere.

This screenshot shows the busy Night City skyline from Cyperpunk 2077. There is so much detail that it takes time to parse. What initially could pass for any modern metropolis is quickly dashed by the ascending holograms and unfamiliar advertising.

Another example from Elite Dangerous is above. Elite Dangerous‘ planet generation is fantastically detailed, and the colour contrast reflecting off the Krait Phantom’s mirrored hull looks wonderful. The distortion from the engine exhaust gives it that extra touch of realism and adds momentum.

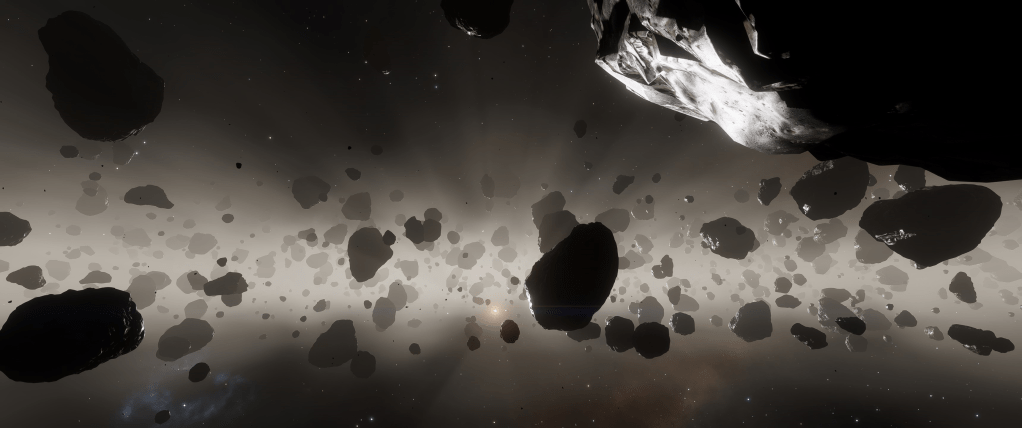

While stark and beautiful, the lack of something interesting in the foreground in the above image gives the feeling something is missing or incomplete.

The best screenshots are not always from the most action-filled or detailed scenes. Screenshots omit many elements of game interaction, reminding us of what the screenshot lacks. There is no movement or action. There is no music, sound effects or story. The hardware sometimes limits the graphical fidelity. A screenshot can expose low polygon models and blurred textures.

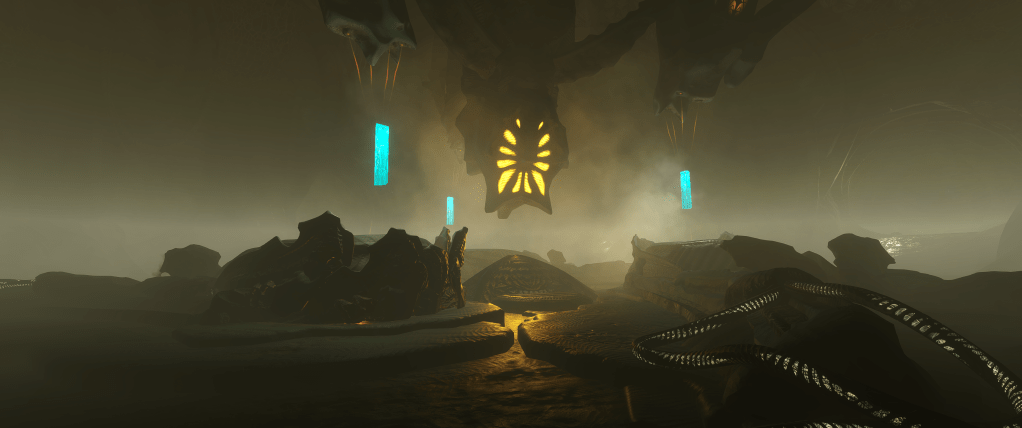

If you have a central focus, viewing it from a slight angle gives it a more natural appearance. It shows more detail from the side or top. The above screenshot shows the misty, creepy, organic, Gieger-esque internals of a thargoid base from Elite Dangerous. The details of the back pillar would otherwise be obscured if the shot was front-on.

The best screenshots tell a story or evoke emotion without context.

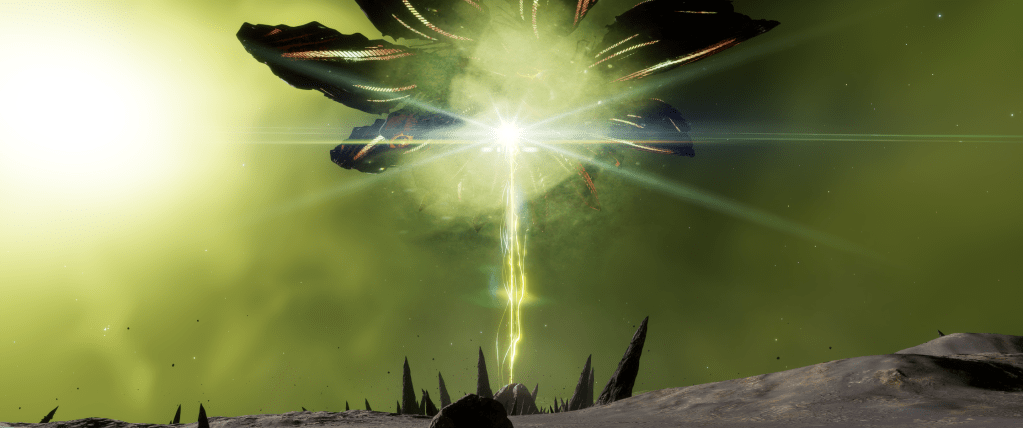

For example, zooming back from the Scorpion (buggy) and placing it below the camera’s centre in the screenshot above draws the eye towards the towering thargoid spire above it. The contrasting light between the green cloud to the right and the blue star to the left pleases the eye. This screenshot evokes a sense of alienness, wonder and being alone.

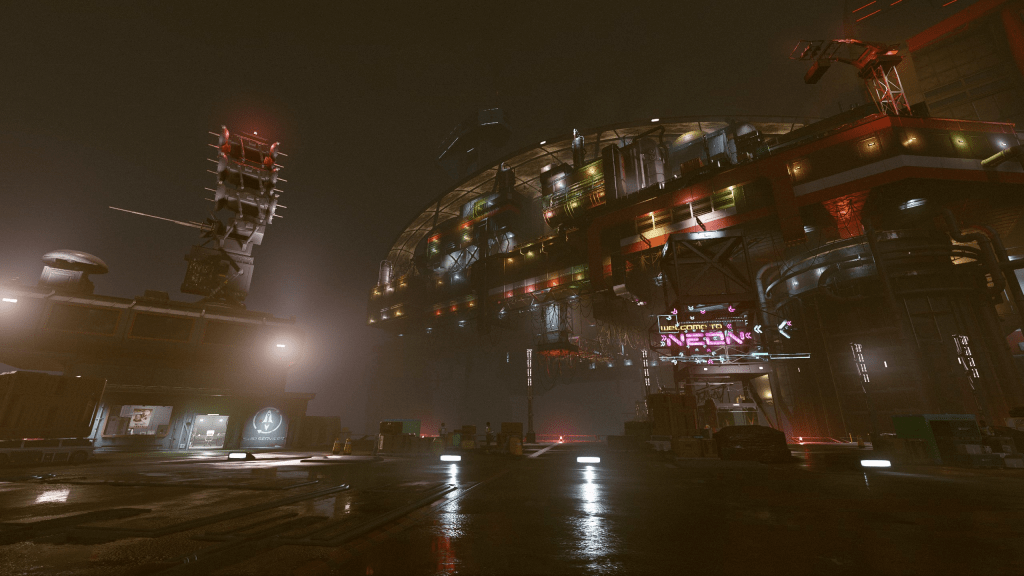

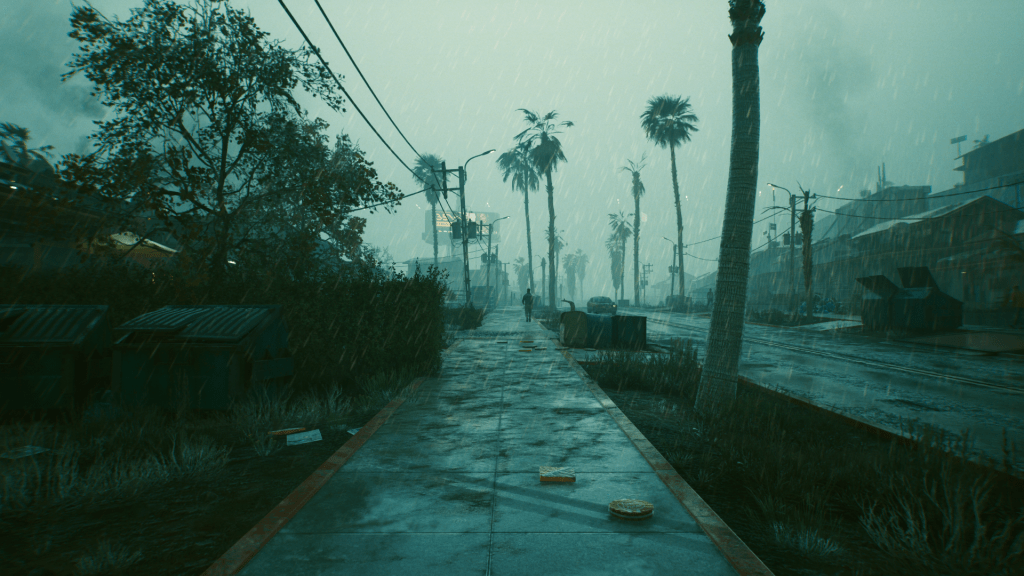

Plenty of games have rain. However, the mist, almost monochromatic palette and subtle reflection in the puddles above capture a dreary oppression better than any other I had seen. The dirty footpath and cluttered scene emphasize the worst parts of urban life.

Avoid busy or unclear scenes. The dozens of spell effects hurled at a boss in an MMORPG raid can be impressive. However, parsing the scene can be difficult. 3D scenes rendered in wide aspect ratios, such as 16:9 or 16:10, distort around the edges. Avoid putting essential details there.

Lighting and colours pose unique challenges and opportunities. Overly dark or light scenes can be hard to discern. Contrasting light can be beautiful, as shown in the dull red of the star against the alien structure’s yellow below. Monochromatic scenes can be stark.

While the scene above has a lot of detail, it is too dark. This is a good example of an HDR scene losing too much contrast when rendered in standard displays.

Disable or remove any “heads-up display”, voice chat overlays or similar UI elements. They often distract from the scene unless they are the focus (“I survived at 1% health!”).

Modern games may have photo modes that temporarily use more screenshot-friendly graphics settings and give more camera control. Use these when you can. Controlling the camera angle or adding effects, such as vignettes or filters, can add a lot.

Tilting the camera turns the already alien world from No Man’s Sky, above, into something disorienting. The slight vignette helps focus the attention on the centre and adds depth.

Effects like bloom, light rays, reflection or lens flare turn a scene into something magical, as shown above. If I ever want new backgrounds for my computer’s desktop, Elite Dangerous is a wonderful way of generating them. Unfortunately, players may have to turn effects off to improve frame rates or to run games on low-end graphics hardware.

Sometimes, careful timing and placement are key. This can be as simple as waiting until night in the first screenshot above or finding a lens-flared eclipse’s exact moment and angle in the second.

Be careful of symbolism and logos in games. While these can be meaningful and emotive in games, they often lose context outside that game. Worse, games sometimes use real-world symbols that can offend.

Avoid modifying screenshots after taking them. Highlight the game developers’ artistry, not Adobe Photoshop skills. Modifications are often prohibited if you want to enter screenshots in competitions. However, each game and community will have its own rules.

Many games have “vista moments”, where the player leaves a cramped, narrow area and enters a broader, almost agoraphobia-inducing wider world. If you are looking to start taking screenshots, finding these is a great place to start. The developers often make these look stunning.

Your first view of the Erdtree in Elden Ring is a wonderful example of a panoramic “vista moment”, as shown above.

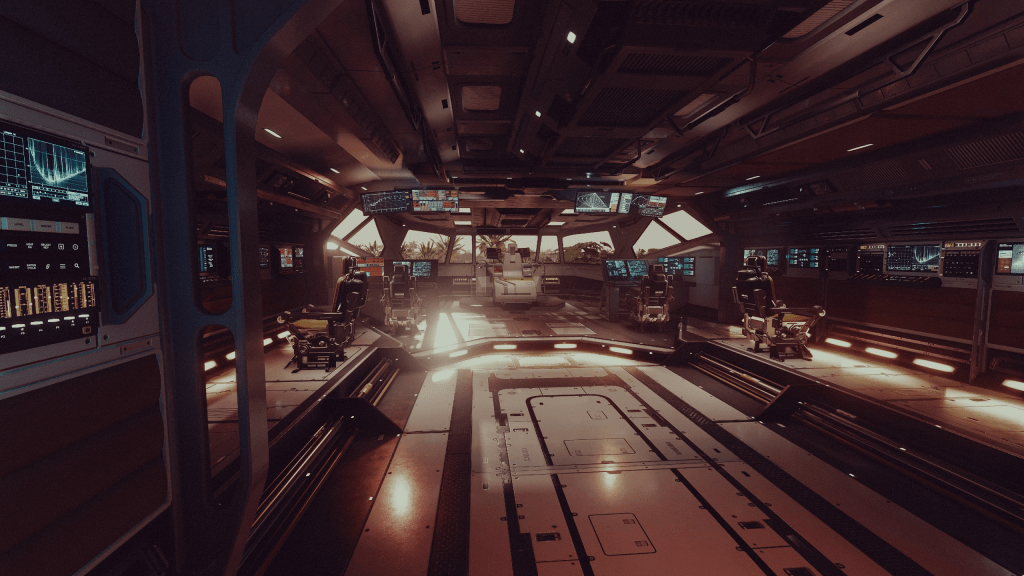

The above scene showing the sun reflecting off the water is a wonderful change from the cramped corridors preceding it. In a setting where the Earth’s environment is collapsing, this reminds you what you are trying to save.

Graphics are arguably the most essential part of video games. While it is possible not to have any significant graphics, e.g. The Vale, video game developers spend much time and resources getting things right that players may only see for a few moments. Taking screenshots both helps share these moments and appreciate the effort and artistry that goes into video game development.