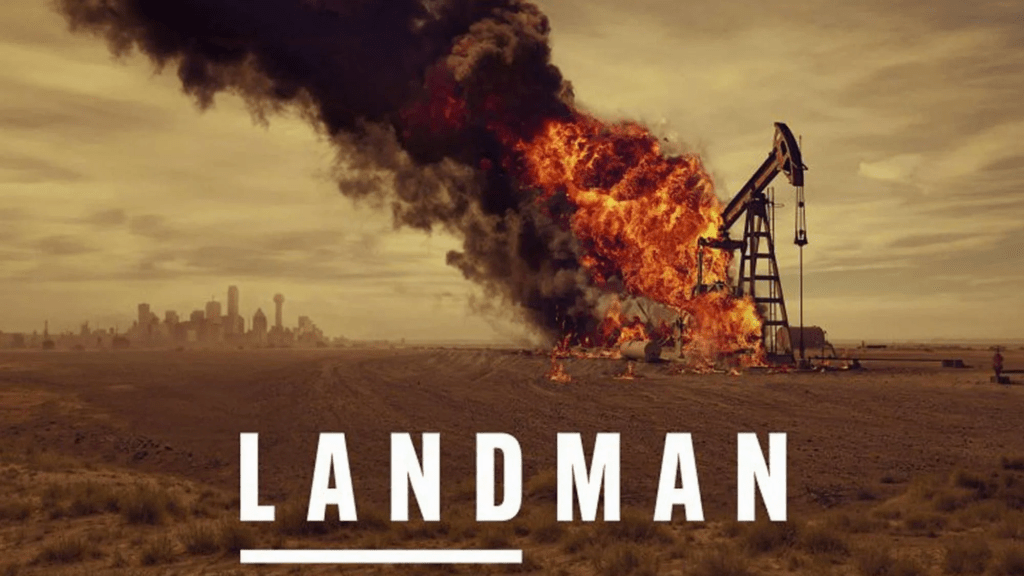

Landman is a gritty drama set in modern-day western Texas centred around a family working in the oil business. Created by Taylor Sheridan, known for shows like Yellowstone and Lioness, Landman shares similar values and a rural, conflict-ridden setting.

Landman follows Tommy Norris, the general manager or “landman” of MTex Oil played perfectly by Billy Bob Thornton, and his family. He deals with personal and professional crises while stoically preventing one from impinging the other.

While Landman has things to say about the oil industry, it has more to say about the people within it. For example, Landman voyeuristically subjects the audience to the brutal lives of the oil field maintenance workers. They endure long hours of physical labour, often with bullying and uncaring bosses and coworkers, while separated from their families. Many are trapped in “the patch” due to criminal records the oil industry is happy to overlook or the salaries that dwarf anything else available.

Meanwhile, the wealthy owners bask in luxury, flying from elaborate lunches to the office in private jets. There is a poignant moment where Tommy, who ensures MTex Oil’s owner never needs to dirty his boots, notices the artwork and finery of his boss’s home. It reminds Tommy of the life that he almost had.

In between, you have Tommy and other professionals working for MTex. They have feet in both worlds. They share a large, spacious house. At first glance, it appears better than the maintenance workers’ accommodation. However, like the maintenance workers, the house is ephemeral (rented), the hours long and the pressure immense.

Landman‘s differing portrayal of men and women is also telling. The men are tough, smoke, drink alcohol and frequently perpetrate and fall victim to violence. They go for the largest, fattiest meals at the pub. The body’s failings are limitations to be ignored, whether they be a broken finger or an ailing heart. Success for a man is determined by wealth, providing for their family and finding the highest strata of society that will accept them.

Success for women, by comparison, is attracting and retaining a successful, wealthy man. They do this via physical attractiveness, spending hours doing cardio in ritzy gyms, and competing with other women to be the most youthful and beautiful. As Angela, Tommy’s soon-to-be ex-ex-wife, says, her job is to provide food, sex and affection. Her husband’s job is to buy or take her where she wants.

Without the mothering of a woman, men often regress, treating unhealthy habits like eating junk food as a badge of honour. Without a man, women lack a place in society.

One exception is Rebecca Savage, a liability attorney called in to help settle a lawsuit after an oil well accident. A woman thrust into a man’s world, Rebecca survives and thrives by being better at her job than men.

Rebecca is also a foil for Tommy and the broader oil industry. She enables exposition, requiring Tommy and others to explain things to an audience surrogate, and acts as an anti-oil industry conscience, countered by Tommy’s pragmatism. She is uncharacteristically a damsel in distress at one point, requiring rescuing by Tommy, which reinforces his masculinity.

Another exception is Cooper Norris, Tommy and Angela’s son. Quitting an almost complete college degree and defying social norms, he starts work on the patch in a maintenance crew. Much to his parent’s dismay, he endures abuse, ridicule and injury to learn the oil business from the bottom up. He quietly sticks to his morals to potentially reap respect and financial rewards, admirably demonstrating his father’s resilience and grit.

This contrasts with Cooper’s sister, Ainsley, whose future success lies in attracting a handsome quarterback. Tommy has to play the traditionally protective father, threatening the boyfriend instead of Ainsley if the relationship goes too far too quickly.

Landman is at its best when it is a pseudo-documentary, usually with Tommy Norris pragmatically explaining the realities of the oil industry and its place in the world. The oil industry is lucrative but slowly dying. The owners lament their grandkids not enjoying their current fortunes. Paradoxically, the world blames the oil industry for its part in climate change but cannot live without it. The overt comparisons with the illicit drug trade are copious.

However, the requisite melodrama and sexualization can drag the show down, particularly in early episodes with Angela. Some would argue that her character is relatably flawed, but no other character requires these to be relatable. Landman is definitely shot for the male gaze. At least Angela got her Bently.

Landman‘s values can be polarizing. For the right wing, Landman is a rebuttal against naive environmentalism. For the left wing, it is a conservative fantasy, glorifying social and economic relics and reinforcing stereotypes. For those who can distance themselves from politics, Landman is a compelling snapshot of a rarely seen slice of America.

Like Taylor Sheridan’s other recent television shows, Landman eschews overly progressive themes, instead focusing on traditional American values and aspirational heroes. However, it succeeds without overt preaching or the seductive lies of nostalgia, common in conservative shows. It is a gritty monument to a people and industry whose days, like suburban coyotes, are numbered.