Starfield is the latest action role playing game (RPG) from Bethesda, the developers of Skyrim and Fallout.

Starfield, the first new RPG setting from Bethesda in a long time, is set in 2330. The Earth’s magnetosphere dissipated over a century earlier, rendering it lifeless. Thankfully, humanity mastered faster-than-light travel via the gravity drive. They rapidly evacuated to the star systems near Earth, deserting old nations and building new institutions.

You start Starfield as a lowly asteroid miner, listening to your coworker’s banter. You unearth a seemingly alien artifact that gives you strange visions. After an attack by space pirates, you are inducted into a quaint, exploration-focused organization called Constellation and whisked off onto an adventure.

Structurally, Starfield has a similar “in media res” style introduction to Skyrim. It quickly teaches you the basic mechanics, gives you a short fight to get the blood pumping, establishes you as the “chosen one”, sets you on the main quest, and then gets out of the way. Much of the exposition happens later.

Starfield‘s strength is the breadth, if not depth, of game loops. Its gameplay is fun, but only exploration is remarkable. The combat is standard first person shooter fare, although melee could be more varied. The stealth mechanics are good but not up to Deus Ex or Cyberpunk 2077. Bethesda nailed the sci-fi feel of lock picking, but once you understand it, less player skill is required than in Skyrim. Your scanner is helpful for exploration, identifying enemies, or satiating hoarding instincts by finding things to pick up.

The gameplay is repetitive but not grindy. You do not need to repeat boring activities to enable more enjoyable gameplay. Sufficient variety in the quests and randomly generated or placed content prevents boredom. Once you exhaust the scripted quests, Starfield offers randomly generated versions to pass the time or continue adventuring. Alternatively, land on a planet and start exploring.

Starfield‘s main quest line is suitably epic and galaxy-spanning, providing mystery and motivation. It draws you above the drama occurring elsewhere in the settled systems. However, this distance means the main quest line loses some emotional grounding and gravitas. Starfield‘s setting and side quests provide the most content, variety and potential like most RPGs.

Starfield contains many visually and thematically diverse places. After leaving the dusty, decrepit asteroid mine and a short detour, you first visit the city of New Atlantis. It is the capital of the United Colonies. Visually, it resembles the citadel from the Mass Effect series: clean, bright, organic curves, open spaces with water and greenery integrated seamlessly with technology.

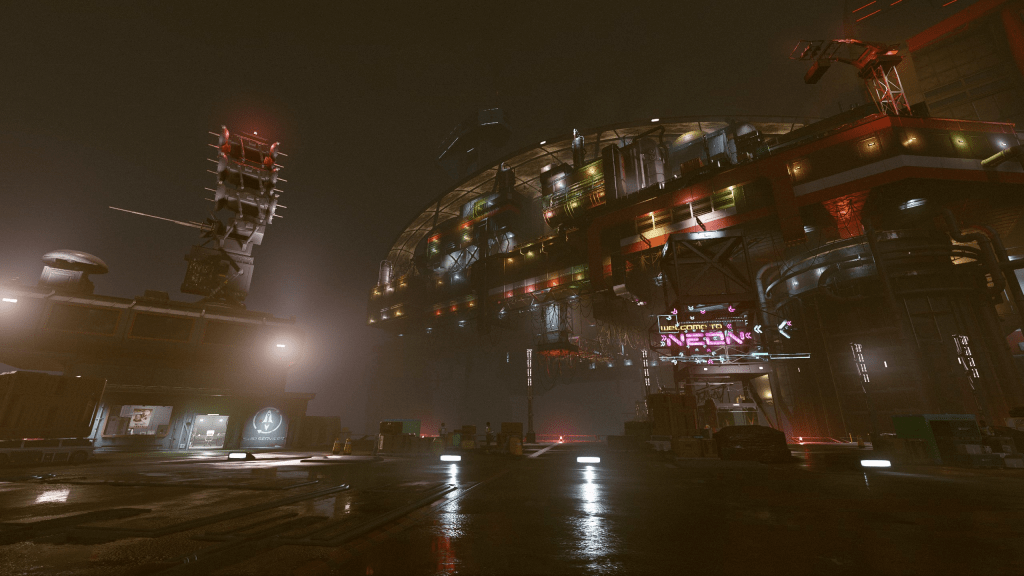

New Atlantis contrasts with other places like Akila City, the capital of the Freestar Collective. Its mud roads and stone buildings make it feel like the Wild West in space, complete with a bank robbery. As its name suggests, Neon is a cyberpunk (the genre) style metropolis on a rain-drenched water world. It is where to indulge in less savoury activities, like gang warfare, corporate espionage, or elicit substances.

Exploration is integral to Starfield, being the primary mission of Constellation. Mechanically, it is similar to No Mans Sky or Elite Dangerous. However, Starfield does it better. Starfield supports multiple biomes per planet, adding variety. Starfield is about exploring a known, finite universe, not the near-infinite set of random ones no one else will ever visit. Planet surfaces intersperse improbably frequent natural phenomena and enemy-filled bases to break up the gameplay. You can improve your exploration skills, like increasing scanner range, sprinting further, or learning more about scanned species.

Starfield is visually better than games like No Mans Sky and Elite Dangerous, and “sense pleasure” is integral to exploration. Not just because Starfield is newer. While all generate terrain procedurally, most of everything else in Starfield is hand-crafted. Starfield‘s alien flora and fauna are more plausible, not just a random assortment of limbs. Think Star Wars, where humanity is not at the top of the food chain. Starfield‘s designers often placed moons and planets to create picturesque views, like ringed planets filling the sky. Starfield also has weather, like dreamy mist-filled sunrises, savage dust storms, or dreary rain.

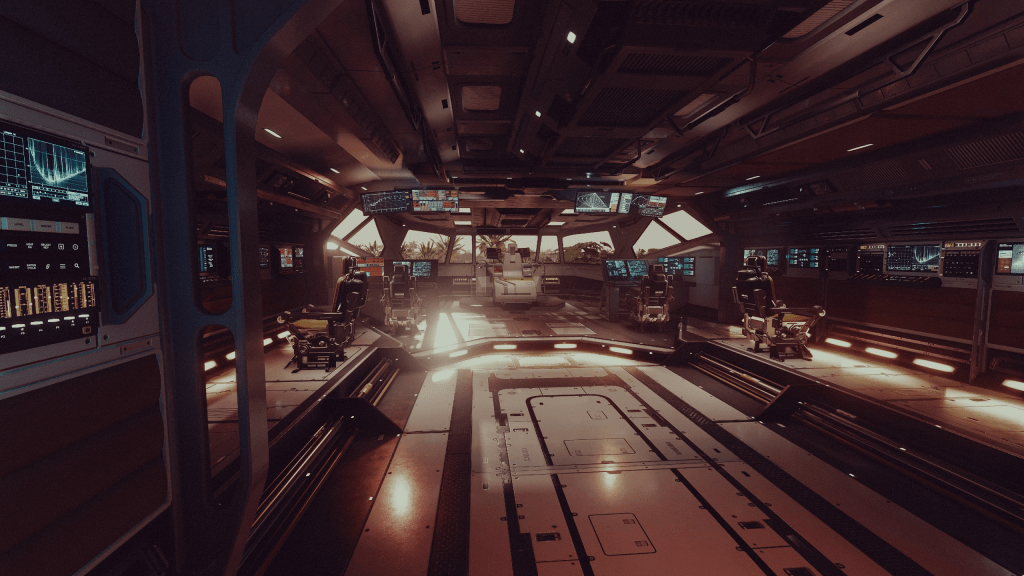

You need a starship to explore. Your starting ship, the Frontier, is a masterful example of worldbuilding. From the venting gas from its landing thrusters, whose exhaust is ignited by sparks like modern rockets, to its white, vaguely aerodynamic shape reminiscent of the space shuttle, it anchors the setting to a believable near future.

Unfortunately, you pilot your ship rarely. It is either in space, docked or landed. Docking and landing are automated. Flying between planets or systems is “fast travel”, using a short cutscene.

Starfield has ship combat, but it is arcade-like and closer to No Mans Sky than Elite Dangerous. It devolves into building ships with better shields and weapons. Manoeuvring is all but useless. The camera views block too much with either the cockpit or your ship’s back. Power management is awkward, particularly in the heat of battle. Macros would be helpful. The targeting mode loses any situational awareness.

However, once you master the clunky interface, the shipbuilder is a beautiful avenue for self-expression. Like the Galactic Civilization franchise, you customize and assemble ships using modular components. In a clever touch of worldbuilding, different vendors’ modules have different styles, such as the blocky, angular Deimos or Taiyo’s almost organic curves.

You can also walk around your ship, board enemy ships and add crafting stations and containers. However, to prevent punishing those with large ships, you can board into or leave directly from the cockpit. Elite Dangerous‘s designers should take note.

Starfield allows building outposts on different planets to store excess equipment, gather resources, craft materials, and refuel ships flying past. You can also create trade links to automate the transfer of materials between them. Starfield almost rivals factory games like Satisfactory with its web of materials and resources.

However, the capacity of even the largest storage buildings needs to increase. A lot. No Mans Sky offers more variety, including positioning individual walls, roof and floor tiles.

In terms of companions, there are dozens that you can hire or find around the galaxy. Of these, four companions have unique quest lines. Each quest line companion follows roughly the same moral compass: generally good and favouring exploration. Although not my thing, this limits the potential for less noble playstyles.

Some want Vasco, your robot companion, to have a quest line and opportunity for growth or change. However, with the world currently enraptured by the potential and danger of AI, seeing a robot follow its programming is a welcome piece of sanity.

Thankfully, Starfield does not take itself too seriously. Catching up with your parents in an alien petting zoo or watching them pretend they did not try illicit substances is touching and amusing. Various “inspirational” posters line the walls of shady secret research labs. Chunks, the ubiquitous cubic fast food of the 24th century, “meet all minimal nutritional requirements”. Vasco has some innocent but cuttingly insightful wit. Your adoring fan’s flattery never gets old.

Starfield‘s music is orchestral, reminiscent of Star Wars or Star Trek. Most tracks are slow and use periodic gradual crescendos to emphasize the wonder and grandeur of Starfield‘s universe. The soundtrack is composed to support a game with lots of voice dialog and critical sound queues, such as in combat. It does not call attention to itself. For example, the restrained, almost mournful menu theme is the opposite of Skyrim‘s rousing call to action. Rather than assaulting the player with aggressive emotion, Starfield‘s version hints that the player has to come to the game (or music), not vice versa.

My main criticism of Starfield is not that it is too easy, at least on “normal” difficulty. I may have played many Bethesda RPGs, but even “hard” provided little challenge. Assuming you do not intentionally engage in challenging content, there is little pressure to specialize your character’s skills, ship, outposts or use consumables for temporary buffs. These become more role playing opportunities.

My main criticism is also not that Starfield is the usual Bethesda RPG oxymoron. Starfield empowers you, creating a feel-good power fantasy where you are important and can make galaxy-affecting changes. However, as the conveniences in your favour accumulate, like free ship fuel or unkillable companions, immersion and suspension of disbelief get harder. Starfields‘ roots in points-based mechanics mean large level differences between you and your target can create unrealistic bullet sponges.

I do not mind that, despite Starfield having the best facial and hair animation of any Bethesda RPG, it still falls into that uncanny valley. NPCs wander aimlessly and still get stuck in walls occasionally.

My main criticism of Starfield is an absent central or recurring theme. For example, in a world where AIs are more intelligent and capable than humans, and the powerful are unshackled from laws and ethics, Cyberpunk 2077 examines humanity. The Fallout series deals with the difficulties of survival and that the best choices are often hard or impossible. The Witcher series shows that, when monsters walk among humans, humans are sometimes the most monstrous of all. The Nier series deals with loss.

In fairness, a game does not need to be profound to be good. Making action movies or games requires skill. Bethesda more than demonstrated it with careful level design, regular mixing of gameplay modes, managing tension, and catering to familiar sci-fi tropes and fantasies. The usual meme-worthy glitches are thankfully absent. The greater attention to quality after Cyberpunk 2077‘s problematic launch is apparent.

Instead, Starfield is pure, fun sci-fi escapism. It is a series of concurrent action movies. RPGs are defined by how well they let you play out fantasies. Starfield delivers on that.

For example, the Vanguard quest line plays like a rerun of Starship Troopers. The Ryujin quest line is a sci-fi James Bond or Mission Impossible coupled with corporate espionage and intrigue. Completing the Mantis quest allows you to play as a space Batman. The Sysdef/Crimson Fleet quest line has palpable tension as you play a double agent, playing criminals and the law against each other. Join the Rangers and play as a space cowboy.

Starfield is unoriginal. Almost everything in the game is “heavily inspired” by something else. That is OK. Successful RPGs help players fulfil fantasies by immersing players in familiar tropes. Where Skyrim opened the fantasy genre to a broader audience, Starfield attempts to do the same with science fiction.

That said, I was disappointed there were not more overt references to other movies, shows or games. Many will pick the few references to Skyrim‘s sweet rolls and Meridia quests. Yes, there was some well-known voice talent from Star Trek: Deep Space 9 and a subtle reference to the 1986 Transformers movie. Cyberpunk 2077 did this comparatively better.

Without strong themes and notwithstanding a few minor nods to modern sensibilities like same-sex relationships, there is little to offend or demand too much of its players. Perhaps Bethesda wanted to play it safe and avoid controversy.

However, Bethesda missed the opportunity to do something more. So many quests touch on real-world themes. For example, the war between the United Colonies and the Freestar Collective that ended 20 years before the game’s start still has lasting social and economic impacts. The United Colonies has to deal with the compromises and the demands strict order creates. The Freestar Collective juggles freedom with the criminal behaviour it facilitates. The Rangers’ quest line deals with the place of veterans in a postwar society. Meanwhile, the wealthy flatter themselves on luxury space cruises.

DLC or the modding community may fill the gap. Like Skyrim and Fallout, Starfield is as much a gaming platform as a game. Much of the work establishes content for future expansion or use. Outposts and shipbuilding, for example, go far beyond what Starfield currently needs. The Va’ruun, relegated to mysterious bogeymen, have much potential.

If you enjoyed Fallout or Skyrim or like science fiction games, you have probably already played or plan to play Starfield. You can race through key quests in 30 hours, but the complete experience takes at least 100 more. Starfield is fun, emphasizes exploration and knows its target audience well. However, the lack of anything original, introspective or thought-provoking may limit its long-term impact on the gaming landscape. Playing Starfield is like eating Chunks. It tastes good and you want more but the nutrition is questionable.

Pingback: Comparing Cyberpunk 2077's Night City to Starfield’s Neon